The second instalment of ‘From the Hills’, is a reflection on what ‘luxury’ means, and a little on England’s meaning too. With a thank you to Harry, at Wakehurst, who gave me many (delightful) hours of his time, and a car ride that saved my day.

We did this walk along the River Arun a while ago now. A three and a half hour ramble by the river, with a couple of hills, in one of the better known towns in this part of West Sussex, Arundel. It is the only consistently busy place we tend to go, and it is funny now to think of how our tastes have evolved. I hadn’t explored the area much, but judging from my walking app, the route was perfect for September weather. Now, the downs here are so familiar that it is strange to imagine it was ever new.

Taking public transport to the Arun valley, as we must, rewards you with post-card English countryside; the towns like little nests in the valleys, the alluring patches of scrub above them, the sheep that pepper the fields. At some point, Arundel castle enters your field of vision, and stays there. Home of the Duke of Norfolk only thanks to it having been gifted (alongside a third of Sussex) to Roger de Montgomery by William the Conqueror, in gratitude for his help with the Norman conquest of England. Perhaps the image of William dividing up England at his table wouldn’t make as popular a post-card, but it would be an accurate depiction of the essence of Englishness nonetheless.

It is not anti-establishment sentiment alone which turns our heads away from its towers; it is what is amongst the fields. It is the little things that charm - like a plain looking field, with a fox laying right at its centre, body curled for slumber; the whole world to itself. We often spot scattered fallow deer, struggling to identify them from roe , or buzzards and sometimes kites, a sign that we are surely moving across the county; the bird life is transforming from our all too familiar seagulls and sparrows. All sightings that feel lucky amid the blurry view from a train window.

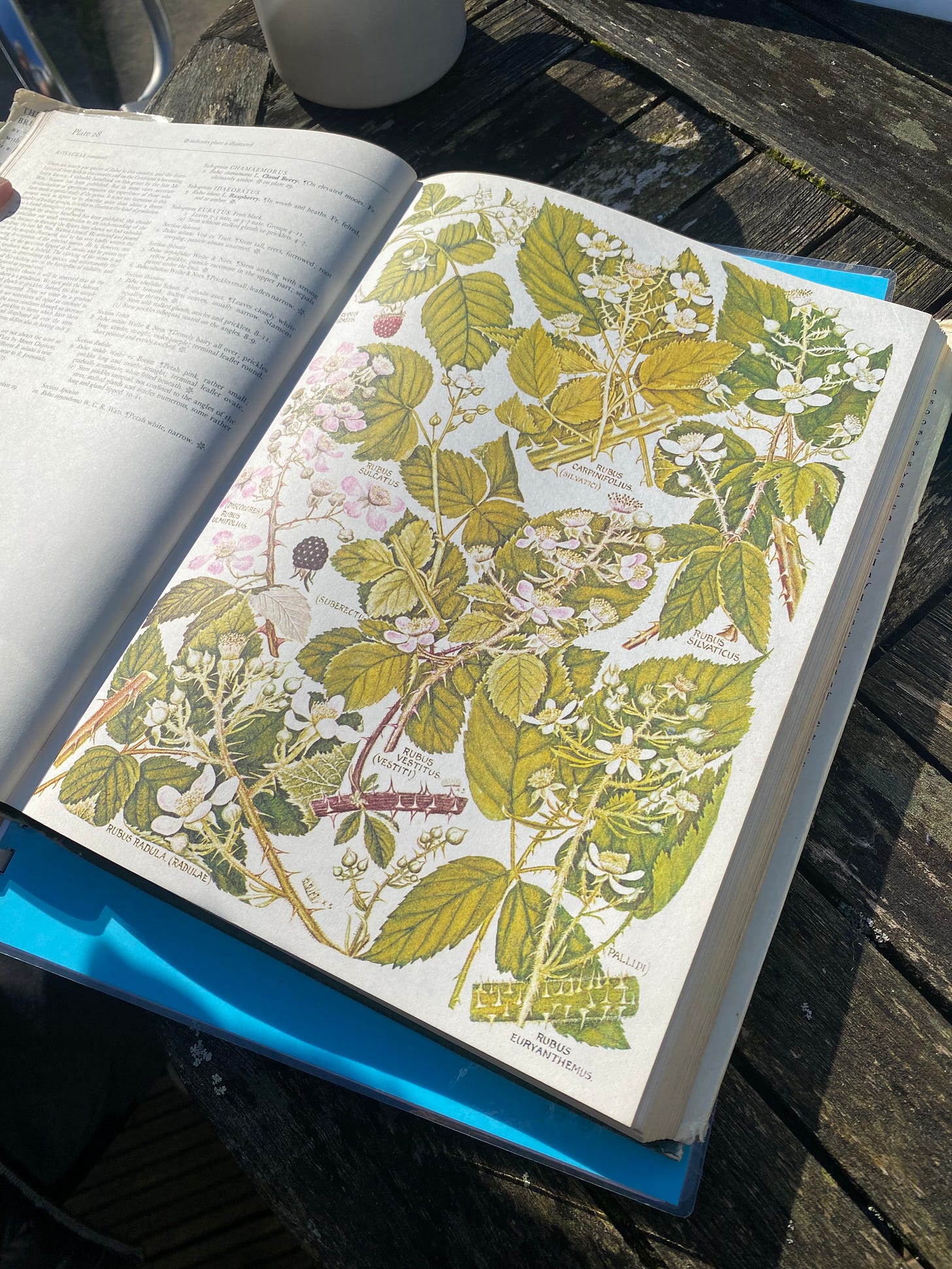

The air smells like September. The riverside and valleys we pass through as we walk confirm my suspicions that blackberries would be abundant here. We take the train home two full tupperwares heavier than when we began. It is almost impossible to take any kind of walk in England without encountering brambles. With my head otherwise dug deep into a dissertation, and all of the stresses that follow from it, blackberry-ing last summer and early autumn provided necessary escapism, the opportunity for which was everywhere, from the gaps in fencing to the expansive hedgerows of the downs. Beyond last year’s season though, blackberries lingered in my thoughts thanks to my incidental introduction to Harry, a librarian at Wakehurst in Sussex. Harry, softly spoken, a researcher of brambles and of ‘cryptic species’ more widely, reels me in with his niche interest immediately. When we meet for a second time to discuss the complexity of bramble species, Harry has a stack of beautiful books with him, some more delicate and old, some written in the last few years. We spend two hours in total, discussing the books, Harry’s research, the Labour party, and who we discover is a mutual favourite environmental historian.

Harry’s main interest is cryptic species, those that taxonomists cannot separate properly, that they cannot explain or understand the relationships between. Harry wants to explore how the label of cryptic species affects our relationship with these things. In one of the books he brings along, for example, the authors write: ‘The average Briton, of either sex, and above the age of ten years, thinks he or she knows a blackberry bush at sight, as well as they know their own reflection in the glass. But the bramble specialist will tell you there are very few botanists who are sufficiently well acquainted with the British brambles to be able to tell you which species you are looking at.’ The book goes on to suggest that it is too complicated for most people to understand, so one might as well think of each bramble bush in the same way. That is one way to look at it.

Harry, on the contrary, tells me about the Trelleck bramble, found on one hill in Wales. The seeds of this very rare plant are actually in the Millenium Seed Bank, at Wakehurst, in an effort to protect it. Despite the fact that the species is endemic only to Trelleck, Gwent, in Wales, a few dedicated people have made a very detailed booklet on it. A garish blue colour on its front, this is definitely a read for the more scientifically-minded. There is also even a journal article on the species, ‘Conservation of Britain's biodiversity: Rubus trelleckensis (Rosaceae), Trelleck Bramble’. Knowing how invasive brambles are, and how often they are torn down in the name of tidiness or practicality, the mind wanders to how many blades have torn through species we didn’t even know we had to lose.

William Morris, a revolutionary, but much more commonly known for his art, once said in a speech, ‘the common people have forgotten what a field or a flower is’. Half of children in Britain now cannot identify brambles, bluebells or nettles, and meanwhile otter, willow and bluebell have been removed from the Oxford Junior Dictionary. Of course, the bramble is recognisable, and it really is unenclosed behind fences and gates - we all still have a relationship to it, we just have no comprehension of its multiplicity. Most Sussex children (and grown ups), for instance, are unlikely to know of the ‘furze-berry’. A vicar and beekeeper from Burpham, Tickner Edwardes, who wrote the book, ‘A Downland Year’ identified this very early blackberry’. ‘Exceptionally big and fine-flavoured’, he notes that nearly all the villagers nearby have their own furzes, ‘whither they resort for blackberries’.

While a species stays cryptic, so many parts of it unknown, it will not make it into conservation policy: ‘People can’t talk about it, because they don’t have a name for it’, says Harry. Do you need to be able to classify something to care about it? In Harry’s words, ‘It is only one way of creating a relationship.’ Ultimately, the people of Trelleck village did need the ability to identify what they came to worship. It is only when I start writing about our conversation that I am reminded of Vandana Shiva: ‘ecological ways of knowing nature are necessarily participatory’; our senses have to really feel something about a particular bramble, or whatever else, in order to feel passionately about them. Noticing the particular pattern of thorns, tracing the edges of a leaf, swirling a berry on your tongue in order to know what unique offering this particular plant provides. A world inhabited by people with this attention to detail, and specifically, to the detail of the plants nearby and in their home, wherever that is, seems an appropriate corrective for the crisis of disconnection we are in.

‘What brings about luxury but a sickly discontent with the simple joys of the lovely earth?’ said William Morris. There is no need to forage for blackberries anymore, because we live in the age of luxury. They are available all year round in the supermarkets, uniform in colour, juicy-looking but generally watery-tasting, and ethically dubious to say the least. One thing you can ensure, they are cheap enough that you can guarantee the price is being paid elsewhere.

In 2023, speaking about undisclosed fruit farms in the South of England, one worker told the House of Lords Horticultural Committee how workers were known by numbers, not by their names. The Landworker’s Alliance report on the fruit picking industry in the UK has stated other terrible crimes against migrants, including debt bondage and racist abuse, all within the fruit picking industry. During the COVID pandemic, the government estimated that only a third of the number of people who would normally have arrived to pick fruit in the UK were available for work. “Pick the sun on your back and the dirt under your nails…Pick being part of something bigger. Pick for Britain” is what the advertisement begging for workers said. The reality is that almost no British workers were hired, the companies and smaller farms chose to continue employing their reliable Eastern European workforce, who were familiar with working conditions, could live on the farm, and had a great deal more experience.

The people who have picked the blackberries we eat suffer on the peripheries of our society. We are told that people of this kind are robbing the average English worker of opportunities, yet they are desperately needed for our lives to be punctuated by plastic-packaged, out-of-season fruits. Robbed of their own stories and humanity, their lives made worse, for ours to be supposedly enriched.

In a country that feels too far from the downs of Sussex to touch us, in 2024, the blackberry industry in Mexico reached a level of success which led to a government-hosted event titled, ‘Our Wealth: The Mexican Blackberry’. ‘Our’ here working to obscure the fact that this agricultural takeover is being spearheaded by huge American corporations like Driscolls, Expoberries, and Hortifrut. The fact that indigenous Mexicans in some of Mexico’s poorest states make up over half of the agricultural workforce is rendered invisible too. One article in the Harvard Review of Latin America states that ‘vast swathes’ of Western Mexico have been transformed into ‘highly mechanized berry production operations.’ In a region troubled by high water stress, the illegal construction of water wells which threaten neighbouring peasants are only one case in point that Mexican workers are only the latest in line to become shock-absorbers for the promise of luxury. From the plastic the berries are packed in, to the refrigeration system and the pesticide use, the industry is growing into ever-larger head of the hydra of environmental injustice and climate change. And you have most likely bought from the companies involved; there is a reason that their workforce targeted the UK for boycott actions - the supermarkets are awash with Driscoll’s.

On the train to Arundel, once you have taken the change at Ford, you will see rows and rows of greenhouses, with what look like empty swimming pools standing just in front. Having passed many times now, we think there are tomatoes in there, maybe some salad leaves too. Each row looks identical, the plants too. The only way to have British grown tomatoes or fruit at any time of the year is extremely energy or water intensive growing. In the limited glimpses that we get, I wonder what chemicals run out of the dirty looking, rusting pipes, and more to the point, where it escapes to once these pools are full to the brim. Half of all blackberries in Europe have residues of the most toxic categories of pesticides (I want to know who is being tasked with spraying them, for in Mexico, exposure to pesticides and the vulnerabilities of the human body is a huge worker concern). A study of fruit and vegetables by the Pesticides Action Network in 2022 showed that there was a 53% rise in contamination from the most hazardous pesticides over the last nine years.

Luxury, William Morris announced in his speech, has ‘blighted the flowers and trees with poisonous gases, and covered green fields ‘with the hovels of slaves’. The photos of Driscoll’s latest land purchases in Mexico remind me of the rows and rows of greenhouses. The most famous lake of Mexico runs dry for a berry overwhelmingly exported to the US, and the UK’s wildlife and health is depleted for something we have in abundance, when the season is right. The end of the world was not as dramatic as we thought; here it is in greenhouses, plastic packaging, and the suffering lungs and backs of the unnamed, unthought of workers.

I have never been inside Arundel castle, and never intend to (opening the doors to the public is how many of the 24 remaining land owning, non-ceremonially titled dukes make more money), but at both the beginning and the end of the walk we take, the castle is what unavoidably dominates. A symbol of English luxury if there ever was one. The dukes’ influence has undoubtedly been reduced in the last two centuries, but we still subsidise them to the sum of £8 million a year. The system of enclosure that began all the way back when William the Conqueror divided up England continues to shape our lives; the same land-grabbing aristocrats have kept this land firmly in their hands - Britain being a close second to the title of most unequally distributed land in the world.

The previous Mexican president led their party’s campaign with the slogan, “Por el bien de todos, primero los pobres” - ‘For the good of everyone, the poor first.’ How would this fare here, in a country where the vast, vast majority of us are land poor, and certainly poor in comparison to the Duke of Norfolk who still sits in his Arundel home. How would we define luxury, if it was no longer in the hands of the powerful?

Blackberries speak to many human complications. Before the ‘revolution of the rich against the poor’ was set in motion by the enclosures, blackberries represented a continuance of a culture of foraging, they provided the sweetness that cradled hard worked bodies through the long day. England is a country of foragers and peasants, of land-hoarders and castle-owning aristocrats, but also of walkers, urban-dwellers, farmers, and foreign fruit pickers; our own multiplicity too often confounded by the likes of right-wing politicians who would prefer a singular story of who we are. The looming climate disaster only deepens the urgency of asking who we could choose to be. What is a better evocation of self and of luxury - a foraged blackberry in the hand, or a view from the gated castle? One embeds oneself deeper into the non-human world, the other seeks to cut oneself off, set oneself apart from what lies outside the walls.

A synonym of cryptic is mystifying, a good word for the power relations we are encouraged not to think of whilst wandering here. Along the river at Arundel, you can choose to see the castle’s shadow wherever you go, or you can get lost in the noise of the reed warblers fidgeting at the water’s edge, in the curves of the hills creating the dramatic shadows into which one can walk, and the comma butterflies flitting between the trees, unwilling to stay still for more than a second. It is getting lost so as to remember that what is contained in the hedgerows is as worthy of our attention as the duke up in the castle, and, in its multiplicity and diversity, certainly more warranting of our admiration.

Morris concluded his speech, ‘Take trouble, and turn your trouble into pleasure: that I shall always hold is the key to a happy life.’ I am thankful, then, for Harry. For troubling the world as I knew it, one with withering diversity, and a population without the access and resources to care for it. The task is to refute singular stories - of what or who is worth sacrificing for the luxury of a few, or simply of how many kinds of blackberries can exist at a time in this world - with the kind of close noticing which Harry clearly lives his life by. I hope his trouble - the fundamental trouble that cryptic species represent - will become a wider pleasure for all of us, eventually. Perhaps we’ll meet again at campaigns for the conservation of our county furze-berry.

Many months later, we are on our last jar of last year’s blackberry jam, and the passing of time has eroded much of the walk’s memory. My camera roll is all I have to fall back on. The photos I took seem to show how the wind swept so beautifully through the grasses that day - as if everything which surrounds the River Arun is breathing the liveliness of the late summer in. And so it should, because Autumn will wither away these thriving greens, the number of birds will rapidly decline, and the rain will make it almost impossible in parts to walk here at all. It feels such a shame as we finish the walk, heading back into the town commanded by the aristocrats of our history and present, that the buzzing in your ears and the soft swishing of the trees is behind us. I head home, weighed down not only by a bag packed full of fruit, but the troubling thoughts of what we define as luxury. A few days later, Mary Oliver’s term for brambles - ‘the black honey of summer’ - feels apt, as we plunge spoons into blackberry cobbler and custard; the thoughts of aristocracy and injustice now mostly gone in a sweet bite, turning instantly, but no doubt superficially (and temporarily), my trouble into pleasure.

An inspiring read